The tight integration of metabolic and cognition-related signals might aid the matching of the brain’s energy supply to its energy needs, by optimizing foraging behaviour and efforts to limit energy expenditure.

The synchronization of glucose supply with brain activity has so far been considered a function of a structure called the hypothalamus, at the base of the brain. Writing in Nature, Tingley et al.3 provide evidence in rats for the role of another brain region, called the hippocampus, which is typically implicated in memory and navigation, in this equation (Fig. 1).

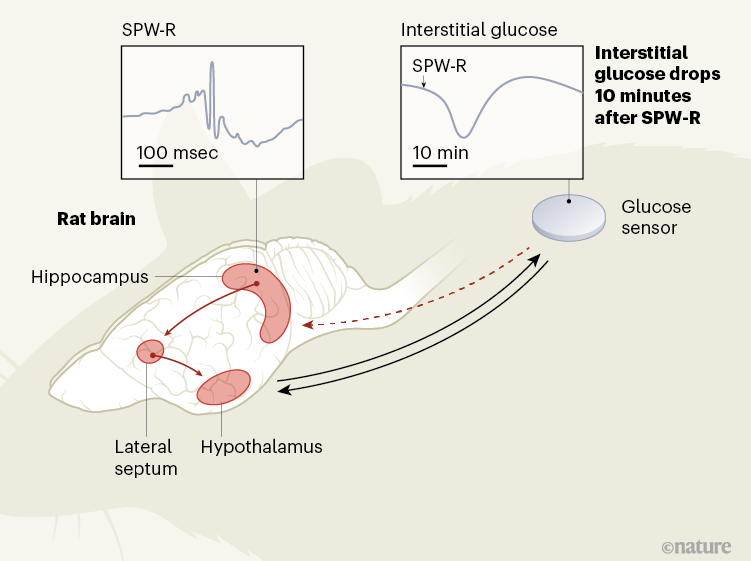

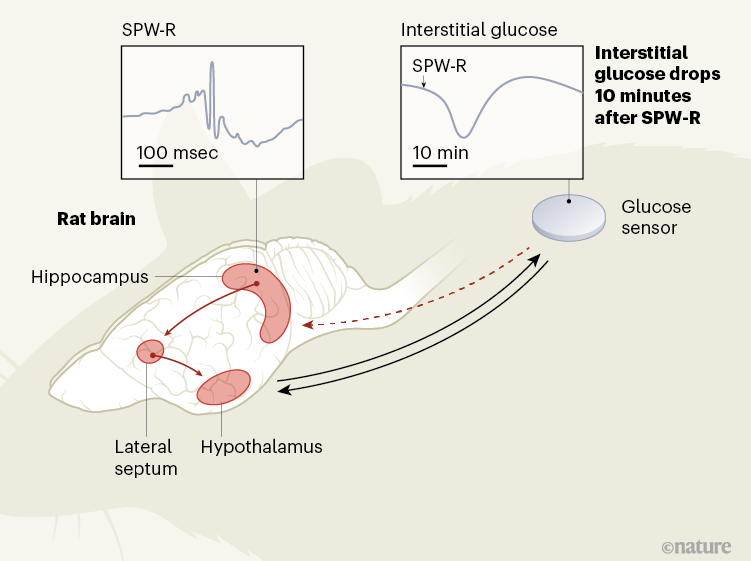

Figure 1 | Brain signals that regulate glucose levels in the body periphery. The hypothalamus in the brain helps to regulate glucose concentrations in the blood and in the interstitial fluid that surrounds cells in the body. This hypothalamic (feedback-mediated) regulation is activated, for example, during stress. Tingley et al.3 provide evidence in rats that another brain structure, the hippocampus, also regulates peripheral glucose concentrations. In the hippocampus, oscillatory patterns — called sharp wave-ripples (SPW-Rs) — emerge in the collective electrical potential across the membranes of neurons. They seem to signal, by way of a region called the lateral septum, to the hypothalamus to produce dips in interstitial glucose concentration about 10 minutes later. The feedback mechanism in this regulatory loop is unknown (dashed arrow). Given that hippocampal SPW-Rs are a hallmark of the reprocessing of previous experiences, they might thus control the brain’s energy supply during a ‘thought-like’ mode.

The hippocampus receives many types of sensory and metabolic information, and projections from neuronal cells in the hippocampus extend to various parts of the brain, including the hypothalamus. Thus, the hippocampus might indeed represent a hub in which metabolic signals are integrated with cognitive processes3.

Figure 1 | Brain signals that regulate glucose levels in the body periphery. The hypothalamus in the brain helps to regulate glucose concentrations in the blood and in the interstitial fluid that surrounds cells in the body. This hypothalamic (feedback-mediated) regulation is activated, for example, during stress. Tingley et al.3 provide evidence in rats that another brain structure, the hippocampus, also regulates peripheral glucose concentrations. In the hippocampus, oscillatory patterns — called sharp wave-ripples (SPW-Rs) — emerge in the collective electrical potential across the membranes of neurons. They seem to signal, by way of a region called the lateral septum, to the hypothalamus to produce dips in interstitial glucose concentration about 10 minutes later. The feedback mechanism in this regulatory loop is unknown (dashed arrow). Given that hippocampal SPW-Rs are a hallmark of the reprocessing of previous experiences, they might thus control the brain’s energy supply during a ‘thought-like’ mode.

The hippocampus receives many types of sensory and metabolic information, and projections from neuronal cells in the hippocampus extend to various parts of the brain, including the hypothalamus. Thus, the hippocampus might indeed represent a hub in which metabolic signals are integrated with cognitive processes3.

To examine this possibility, Tingley and colleagues recorded oscillatory patterns called sharp wave-ripples (SPW-Rs), reflecting changes in electrical potential across the cell membranes of neuronal-cell ensembles in the hippocampi of rats. They did this while using a sensor inserted under the skin of the animals’ backs to continuously measure glucose levels in the interstitial fluid surrounding the cells there. READ MORE

No comments:

Post a Comment