Tuesday, January 11

Monday, January 10

Not From Viking Civilization

The two Viksø helmets were found in pieces a bog in eastern Denmark in 1942. Archaeologists think they were deliberately deposited there as religious offerings. (Image credit: National Museum of Denmark)

Two spectacular bronze helmets decorated with bull-like, curved horns may have inspired the idea that more than 1,500 years later, Vikings wore bulls' horns on their helmets, although there is no evidence they ever did.

Rather, the two helmets were likely emblems of the growing power of leaders in Bronze Age Scandinavia.

In 1942, a worker cutting peat for fuel discovered the helmets — which sport "eyes" and "beaks" — in a bog near the town of Viksø (also spelled Veksø) in eastern Denmark, a few miles northwest of Copenhagen. The helmets' design suggested to some archaeologists that the artifacts originated in the Nordic Bronze Age (roughly from 1750 B.C. to 500 B.C.), but until now no firm date had been determined. The researchers of the new study used radiocarbon methods to date a plug of birch tar on one of the horn

"For many years in popular culture, people associate the Viksø helmets with the Vikings," said Helle Vandkilde, an archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark. "But actually, it's nonsense. The horned theme is from the Bronze Age and is traceable back to the ancient Near East."

The new research by Vandkilde and her colleagues confirms that the helmets were deposited in the bog in about 900 B.C. — almost 3,000 years ago and many centuries before the Vikings or Norse dominated the region.

That dates the helmets to the late Nordic Bronze Age, a time when archaeologists think the regular trade of metals and other items had become common throughout Europe and foreign ideas were influencing Indigenous cultures, the researchers wrote in the journal Praehistorische Zeitschrift. TO READ MORE ABOUT THIS, CLICK HERE...

Two spectacular bronze helmets decorated with bull-like, curved horns may have inspired the idea that more than 1,500 years later, Vikings wore bulls' horns on their helmets, although there is no evidence they ever did.

Rather, the two helmets were likely emblems of the growing power of leaders in Bronze Age Scandinavia.

In 1942, a worker cutting peat for fuel discovered the helmets — which sport "eyes" and "beaks" — in a bog near the town of Viksø (also spelled Veksø) in eastern Denmark, a few miles northwest of Copenhagen. The helmets' design suggested to some archaeologists that the artifacts originated in the Nordic Bronze Age (roughly from 1750 B.C. to 500 B.C.), but until now no firm date had been determined. The researchers of the new study used radiocarbon methods to date a plug of birch tar on one of the horn

"For many years in popular culture, people associate the Viksø helmets with the Vikings," said Helle Vandkilde, an archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark. "But actually, it's nonsense. The horned theme is from the Bronze Age and is traceable back to the ancient Near East."

The new research by Vandkilde and her colleagues confirms that the helmets were deposited in the bog in about 900 B.C. — almost 3,000 years ago and many centuries before the Vikings or Norse dominated the region.

That dates the helmets to the late Nordic Bronze Age, a time when archaeologists think the regular trade of metals and other items had become common throughout Europe and foreign ideas were influencing Indigenous cultures, the researchers wrote in the journal Praehistorische Zeitschrift. TO READ MORE ABOUT THIS, CLICK HERE...

Quantum Tornados

Scientists have observed a stunning demonstration of classic physics giving way to quantum behavior, manipulating a fluid of ultra-cold sodium atoms into a distinct tornado-like formation.

Particles behave differently on the quantum level, in part because at this point their interactions with each other hold more power over them than the energy from their movement.

Then, of course, there's the mind-boggling fact that quantum particles don't exactly have a certain fixed location like you or I, which influences how they interact.

By cooling particles down to as close to absolute zero as possible and eliminating other interference, physicists can observe what happens when these strange interactions take hold, as a team from MIT has just done.

"It's a breakthrough to be able to see these quantum effects directly," says MIT physicist Martin Zwierlein.

The team trapped and spun a cloud of around 1 million sodium atoms using lasers and electromagnets. In previous research physicists demonstrated this would spin the cloud into a long needle-like structure, a Bose-Einstein condensate, where the gas starts to behave like a single entity with shared properties.

"In a classical fluid, like cigarette smoke, it would just keep getting thinner," says Zwierlein. "But in the quantum world, a fluid reaches a limit to how thin it can get."

In the new study, MIT physicist Biswaroop Mukherjee and colleagues pushed beyond this stage, capturing a series of absorption images that reveal what happens after atoms' have switched from being predominantly governed by classical to quantum physics. READ MORE...

Revenge is Coming

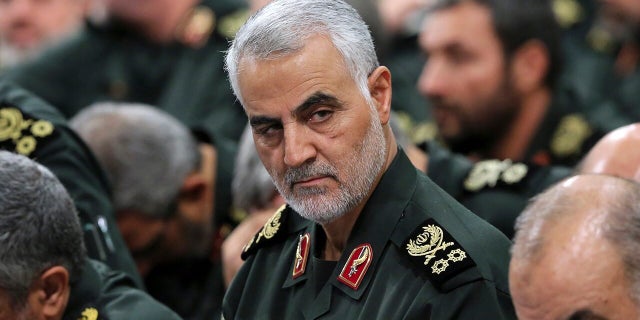

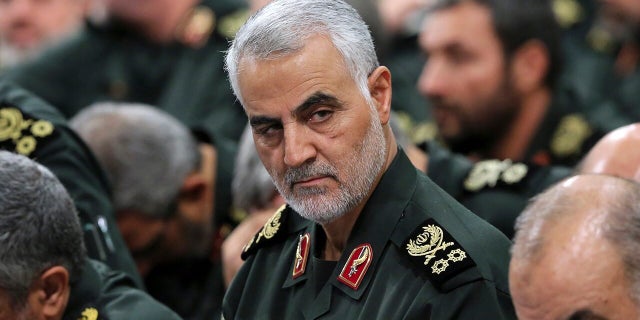

The leader of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps has warned that revenge for Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani’s death will come for the United States from "within" the country itself.

Soleimani, head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Forces, was killed in a Jan. 3, 2020, U.S. strike in Baghdad, days after Iranian-backed militia supporters stormed the U.S. Embassy in Iraq.

Brig. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, head of Iran’s elite Quds force, gives a speech during a ceremony to mark the one-year anniversary of the killing of senior Iranian military commander Gen. Qassem Soleimani in a U.S. attack, in Tehran, Jan. 1, 2021. (Reuters)

Brig. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, who replaced Soleimani, spoke during the second anniversary of Soleimani’s death, which Iran has labeled as "martyrdom." Ghaani underscored the republic’s dedication to avenging the general’s death, saying that the "ground for the hard revenge" will come from "within" the homes of Americans.

"We do not need to be present as supervisors everywhere, wherever is necessary we take revenge against Americans by the help of people on their side and within their own homes without our presence," Ghaani said, according to Tasnim News.

Iran's Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani was killed in a U.S. attack in Baghdad in January 2020.

He urged the United States to "deal" with those involved in Soleimani’s "assassination" itself before the "children of the Resistance Front" need to take matters into their own hands.

"This revenge has begun," Ghaani added. "Americans will be uprooted from the region."

The Tasnim News Agency is a private agency owned by the Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organization, which claims to defend "the Islamic Revolution against negative media propaganda campaign and providing … readers with realities on the ground about Iran and Islam."

Soleimani, head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Forces, was killed in a Jan. 3, 2020, U.S. strike in Baghdad, days after Iranian-backed militia supporters stormed the U.S. Embassy in Iraq.

Brig. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, head of Iran’s elite Quds force, gives a speech during a ceremony to mark the one-year anniversary of the killing of senior Iranian military commander Gen. Qassem Soleimani in a U.S. attack, in Tehran, Jan. 1, 2021. (Reuters)

Brig. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, who replaced Soleimani, spoke during the second anniversary of Soleimani’s death, which Iran has labeled as "martyrdom." Ghaani underscored the republic’s dedication to avenging the general’s death, saying that the "ground for the hard revenge" will come from "within" the homes of Americans.

"We do not need to be present as supervisors everywhere, wherever is necessary we take revenge against Americans by the help of people on their side and within their own homes without our presence," Ghaani said, according to Tasnim News.

Iran's Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani was killed in a U.S. attack in Baghdad in January 2020.

He urged the United States to "deal" with those involved in Soleimani’s "assassination" itself before the "children of the Resistance Front" need to take matters into their own hands.

"This revenge has begun," Ghaani added. "Americans will be uprooted from the region."

The Tasnim News Agency is a private agency owned by the Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organization, which claims to defend "the Islamic Revolution against negative media propaganda campaign and providing … readers with realities on the ground about Iran and Islam."

Sunday, January 9

Math Is A Fundamental Part of Nature

Nature is an unstoppable force, and a beautiful one at that. Everywhere you look, the natural world is laced with stunning patterns that can be described with mathematics. From bees to blood vessels, ferns to fangs, math can explain how such beauty emerges.

Math is often described this way, as a language or a tool that humans created to describe the world around them, with precision.

But there's another school of thought which suggests math is actually what the world is made of; that nature follows the same simple rules, time and time again, because mathematics underpins the fundamental laws of the physical world.

This would mean math existed in nature long before humans invented it, according to philosopher Sam Baron of the Australian Catholic University.

"If mathematics explains so many things we see around us, then it is unlikely that mathematics is something we've created," Baron writes.

Instead, if we think of math as an essential component of nature that gives structure to the physical world, as Baron and others suggest, it might prompt us to reconsider our place in it rather than reveling in our own creativity.

(Westend61/Getty Images)

(Westend61/Getty Images)

Math is often described this way, as a language or a tool that humans created to describe the world around them, with precision.

But there's another school of thought which suggests math is actually what the world is made of; that nature follows the same simple rules, time and time again, because mathematics underpins the fundamental laws of the physical world.

This would mean math existed in nature long before humans invented it, according to philosopher Sam Baron of the Australian Catholic University.

"If mathematics explains so many things we see around us, then it is unlikely that mathematics is something we've created," Baron writes.

Instead, if we think of math as an essential component of nature that gives structure to the physical world, as Baron and others suggest, it might prompt us to reconsider our place in it rather than reveling in our own creativity.

(Westend61/Getty Images)

(Westend61/Getty Images)A world made of math

This thinking dates back to Greek philosopher Pythagoras (around 575-475 BCE), who was the first to identify mathematics as one of two languages that can explain the architecture of nature; the other being music. He thought all things were made of numbers; that the Universe was 'made' of mathematics, as Baron puts it.

More than two millennia later, scientists are still going to great lengths to uncover where and how mathematical patterns emerge in nature, to answer some big questions – like why cauliflowers look oddly perfect.

This thinking dates back to Greek philosopher Pythagoras (around 575-475 BCE), who was the first to identify mathematics as one of two languages that can explain the architecture of nature; the other being music. He thought all things were made of numbers; that the Universe was 'made' of mathematics, as Baron puts it.

More than two millennia later, scientists are still going to great lengths to uncover where and how mathematical patterns emerge in nature, to answer some big questions – like why cauliflowers look oddly perfect.

TO READ MORE ABOUT THE FUNDAMENTAL PART OF NATURE, CLICK HERE...

Panic Buying & Isolation Dodging

‘Live your life as though your every act were to become a universal law’. EPA/ Salvatore Di Nolfi

‘Live your life as though your every act were to become a universal law’. EPA/ Salvatore Di NolfiThe coronavirus crisis has forced us to look at our behaviour in a way that we’re not used to. We are being asked to act in the collective good rather than our individual preservation and interest. Even for those of us with the best of intentions, this is not so easy.

This is a problem for governments. Practically, they need us to obey their recommendations and to only buy what we need. They can enforce these behaviours upon us through policing, but some, such as the UK government, have preferred to appeal to our sense of duty and morality to act in the interest of society as a whole. They say “we have to ask you” rather than “you must”. They are invoking a communal spirit to do what’s right. The key point being that we should follow guidelines out of a sense of duty rather than needing to be commanded. Judging from the fact that I am having to ration my coffee supply, this is having mixed success.

Friederich Nietzsche argues that appeals to morality are no less a system of power and discipline than the police. In his book The Genealogy of Morals, he argues that moral thinking arises first, not from a desire to be a good and happy human being, but from the upper classes as a way of distinguishing themselves from the lower classes – justifying why they had benefits those less fortunate did not.

He points out that, in most languages, the words for good and evil arise from the words for “clean” and “unclean”. The evidence of the moral nobility of the upper classes was their cleanliness and the decadence of the lower classes was proven by their dirtiness. This still seems to be true today, as we are told it is a moral duty to be clean and that those who do not obey the bodily discipline of handwashing, facial awareness and social distancing are not simply dangerous but selfish. READ MORE..

Lake Atagahi

The secret lake hidden in the Smoky Mountains

Legend states that Atagahi Lake was shallow, purple, and fed by mountain springs (photo by Petr Jelinek/stock.adobe.com)

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is dotted with well-preserved conclaves of cabins and barns. And the occasional mill or silo.

Places like Cades Cove or Greenbrier or Roaring Fork serve as reminders of life in the mountains in the decades leading up to the formation of the park.

And as we walk through these places, running our hands along the rough-hewn wood, feeling the planks creaking beneath our feet and feeling the crisp breath of a breeze blowing through, we try to imagine ourselves living in such a time and such a place.

In fact, it is impossible for most of us. READ MORE...

Legend states that Atagahi Lake was shallow, purple, and fed by mountain springs (photo by Petr Jelinek/stock.adobe.com)

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is dotted with well-preserved conclaves of cabins and barns. And the occasional mill or silo.

Places like Cades Cove or Greenbrier or Roaring Fork serve as reminders of life in the mountains in the decades leading up to the formation of the park.

And as we walk through these places, running our hands along the rough-hewn wood, feeling the planks creaking beneath our feet and feeling the crisp breath of a breeze blowing through, we try to imagine ourselves living in such a time and such a place.

In fact, it is impossible for most of us. READ MORE...

Saturday, January 8

Stellar Cocoon With Organic Molecules

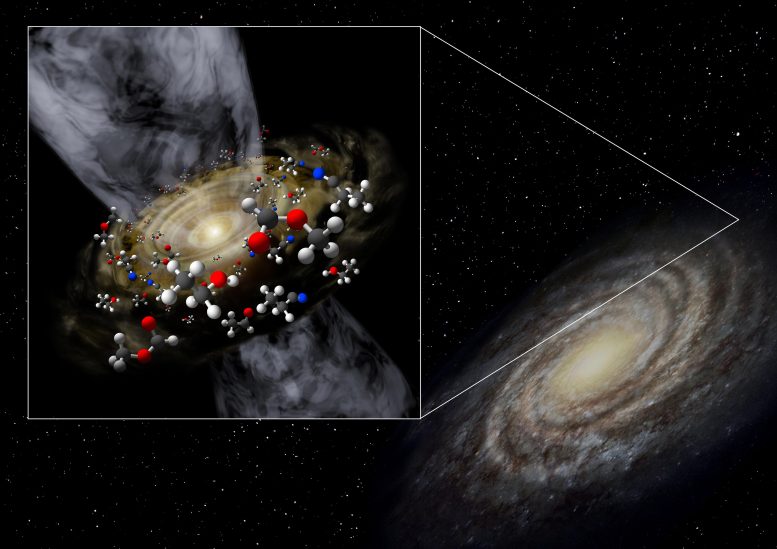

Artist’s conceptual image of the protostar discovered in the extreme outer Galaxy. Credit: Niigata University

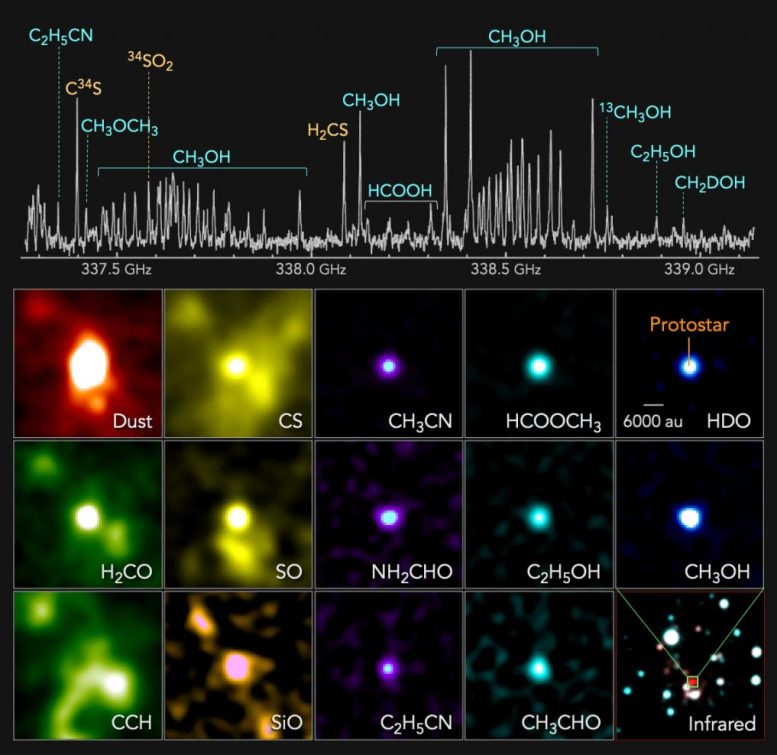

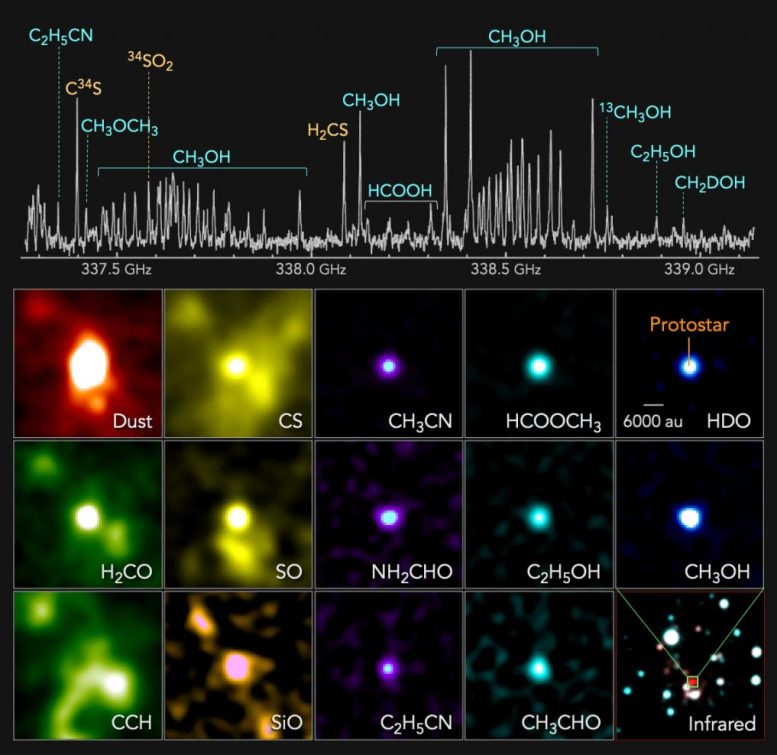

For the first time, astronomers have detected a newborn star and the surrounding cocoon of complex organic molecules at the edge of our Galaxy, which is known as the extreme outer Galaxy. The discovery, which revealed the hidden chemical complexity of our Universe, appears in a paper in The Astrophysical Journal.

The scientists from Niigata University (Japan), Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (Taiwan), and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to observe a newborn star (protostar) in the WB89-789 region, located in the extreme outer Galaxy.

A variety of carbon-, oxygen-, nitrogen-, sulfur-, and silicon-bearing molecules, including complex organic molecules containing up to nine atoms, were detected. Such a protostar, as well as the associated cocoon of chemically-rich molecular gas, were for the first time detected at the edge of our Galaxy.

The ALMA observations reveal that various kinds of complex organic molecules, such as methanol (CH3OH), ethanol (C2H5OH), methyl formate (HCOOCH3), dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3), formamide (NH2CHO), propanenitrile (C2H5CN), etc., are present even in the primordial environment of the extreme outer Galaxy. Such complex organic molecules potentially act as the feedstock for larger prebiotic molecules.

Top: Radio spectrum of a protostar in the extreme outer Galaxy discovered with ALMA. Bottom: Distributions of radio emissions from the protostar. Emissions from dust, formaldehyde (H2CO), ethynylradical (CCH), carbon monosulfide (CS), sulfur monoxide (SO), silicon monoxide (SiO), acetonitrile (CH3CN), formamide (NH2CHO), propanenitrile (C2H5CN), methyl formate (HCOOCH3), ethanol (C2H5OH), acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), deuterated water (HDO), and methanol (CH3OH) are shown as examples. In the bottom right panel, an infrared 2-color composite image of the surrounding region is shown (red: 2.16 μm and blue: 1.25 μm, based on 2MASS data). Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), T. Shimonishi (Niigata University)

The ALMA observations reveal that various kinds of complex organic molecules, such as methanol (CH3OH), ethanol (C2H5OH), methyl formate (HCOOCH3), dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3), formamide (NH2CHO), propanenitrile (C2H5CN), etc., are present even in the primordial environment of the extreme outer Galaxy. Such complex organic molecules potentially act as the feedstock for larger prebiotic molecules.

Top: Radio spectrum of a protostar in the extreme outer Galaxy discovered with ALMA. Bottom: Distributions of radio emissions from the protostar. Emissions from dust, formaldehyde (H2CO), ethynylradical (CCH), carbon monosulfide (CS), sulfur monoxide (SO), silicon monoxide (SiO), acetonitrile (CH3CN), formamide (NH2CHO), propanenitrile (C2H5CN), methyl formate (HCOOCH3), ethanol (C2H5OH), acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), deuterated water (HDO), and methanol (CH3OH) are shown as examples. In the bottom right panel, an infrared 2-color composite image of the surrounding region is shown (red: 2.16 μm and blue: 1.25 μm, based on 2MASS data). Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), T. Shimonishi (Niigata University)

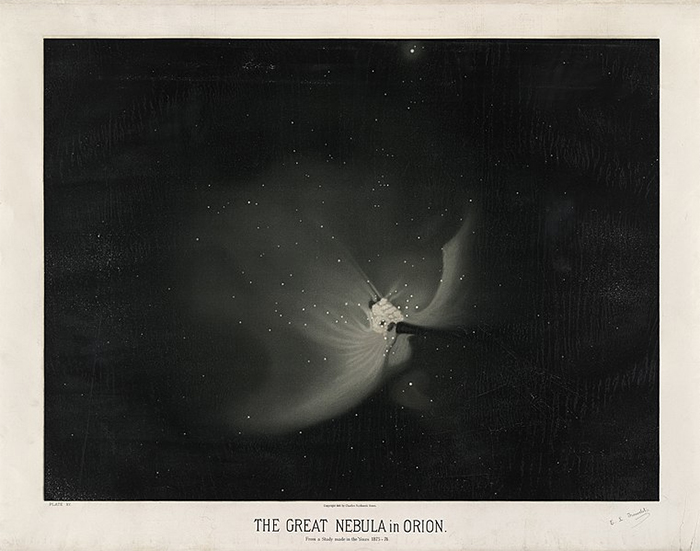

Space Art

Astrophotography allows us all to become citizens of the cosmos.

At a glimpse, we can be transported into the depths of space to gaze upon Jupiter's dazzling cloudscape. Moments later we can picture the shifting rust-colored sands of Mars, or navigate our way across the lunar surface.

It's a gift that's easy to take for granted. After all, a century and a half ago it took the creative hand of a talented artist to preserve what only a privileged few ever got to see; a hand not unlike Étienne Léopold Trouvelot's.

Born in France in 1827, the lithography printer fled to America with his wife Adele following a coup by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in 1851. There, a brief foray into entomology would have devastating consequences for his new home, leading Trouvelot to return to old passions – art and astronomy.

At a time when photography was in its infancy and even the best telescopes were little more than finely crafted lenses, there was no substitute for a generous dose of artistic license when it came to preserving what the eye saw.

"A well-trained eye alone is capable of seizing the delicate details of structure and of configuration of the heavenly bodies, which are liable to be affected, and even rendered invisible, by the slightest changes in our atmosphere," Trouvelot wrote of his work.

Today, his astronomical artworks can still stir up emotions of awe and wonder over the stunning beauty of stars and gas clouds few have the fortune of seeing first hand.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)Or his intricate mapping of the texture of a Moon so many of us are familiar with, but rarely see up close. READ MORE...

Using A Drunkard's Walk

(Image credit: Adrienne Bresnahan/Getty Images)

A physics problem that has plagued science since the days of Isaac Newton is closer to being solved, say a pair of Israeli researchers. The duo used "the drunkard's walk" to calculate the outcome of a cosmic dance between three massive objects, or the so-called three-body problem.

For physicists, predicting the motion of two massive objects, like a pair of stars, is a piece of cake. But when a third object enters the picture, the problem becomes unsolvable. That's because when two massive objects get close to each other, their gravitational attraction influences the paths they take in a way that can be described by a simple mathematical formula. But adding a third object isn't so simple: Suddenly, the interactions between the three objects become chaotic.

Instead of following a predictable path defined by a mathematical formula, the behavior of the three objects becomes sensitive to what scientists call "initial conditions" — that is, whatever speed and position they were in previously. Any slight difference in those initial conditions changes their future behavior drastically, and because there's always some uncertainty in what we know about those conditions, their behavior is impossible to calculate far out into the future.

In one scenario, two of the objects might orbit each other closely while the third is flung into a wide orbit; in another, the third object might be ejected from the other two, never to return, and so on.

In a paper published in the journal Physical Review X, scientists used the frustrating unpredictability of the three-body problem to their advantage.

To do that, they relied on the theory of random walks — also known as "the drunkard's walk." The idea is that a drunkard walks in random directions, with the same chance of taking a step to the right as taking a step to the left. If you know those chances, you can calculate the probability of the drunkard ending up in any given spot at some later point in time.

So in the new study, Ginat and Perets looked at systems of three bodies, where the third object approaches a pair of objects in orbit. In their solution, each of the drunkard's "steps" corresponds to the velocity of the third object relative to the other two.

"One can calculate what the probabilities for each of those possible speeds of the third body is, and then you can compose all those steps and all those probabilities to find the final probability of what's going to happen to the three-body system in a long time from now," meaning whether the third object will be flung out for good, or whether it might come back, for instance, Ginat said. READ MORE...

In a paper published in the journal Physical Review X, scientists used the frustrating unpredictability of the three-body problem to their advantage.

"[The three-body problem] depends very, very sensitively on initial conditions, so essentially it means that the outcome is basically random," said Yonadav Barry Ginat, a doctoral student at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology who co-authored the paper with Hagai Perets, a physicist at the same university. "But that doesn't mean that we cannot calculate what probability each outcome has."

To do that, they relied on the theory of random walks — also known as "the drunkard's walk." The idea is that a drunkard walks in random directions, with the same chance of taking a step to the right as taking a step to the left. If you know those chances, you can calculate the probability of the drunkard ending up in any given spot at some later point in time.

So in the new study, Ginat and Perets looked at systems of three bodies, where the third object approaches a pair of objects in orbit. In their solution, each of the drunkard's "steps" corresponds to the velocity of the third object relative to the other two.

"One can calculate what the probabilities for each of those possible speeds of the third body is, and then you can compose all those steps and all those probabilities to find the final probability of what's going to happen to the three-body system in a long time from now," meaning whether the third object will be flung out for good, or whether it might come back, for instance, Ginat said. READ MORE...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)